The European Volunteer Movement in World War IIRichard Landwehr |

They

called themselves the "assault generation" and they had largely been born

in the years during and after World War I. Coming from every nation of

Europe, they had risen up against the twin hydra of communism and big capitalism

and banded together under one flag for a common cause. Fully a million

of them joined the German Army in World War II, nearly half of them with

the Waffen-SS. And it was in the Waffen-SS, the elite fighting force of

Germany, where the idea of a united, anti-communist Europe became fully

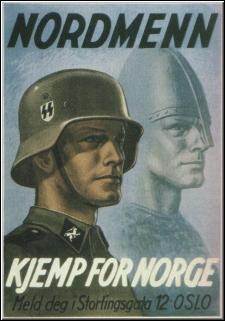

developed. [Image: Norwegian SS Recruiting Poster -- "Fight for Norway".] They

called themselves the "assault generation" and they had largely been born

in the years during and after World War I. Coming from every nation of

Europe, they had risen up against the twin hydra of communism and big capitalism

and banded together under one flag for a common cause. Fully a million

of them joined the German Army in World War II, nearly half of them with

the Waffen-SS. And it was in the Waffen-SS, the elite fighting force of

Germany, where the idea of a united, anti-communist Europe became fully

developed. [Image: Norwegian SS Recruiting Poster -- "Fight for Norway".]

It was also in the Waffen-SS where a new society emerged from among the "front fighters" of thirty different nations. It was a society that had been forged in the sacrifice, sweat and blood of the battlefield and that propagated the concept of "one new race," the European race, wherein language and national differences counted for little, while the culture of each nation was taken for granted as a common heritage. Many countries sent more volunteers into the Waffen-SS than they could raise for their own national armies, so something truly phenomenal was taking place. The Waffen-SS itself was something unusually special. It had started out as a small-sized personal bodyguard for Adolf Hitler but had gradually expanded into a full-scale military force under the guidance of a number of disgruntled former army officers who saw the Waffen-SS as a chance to break out from the conservative mold that the German Army had become mired in. The Waffen-SS was designed from the start to be a highly mobile assault force whose soldiers were well versed in the art of handling modern, close-combat weapons. The training regimen therefore resembled that given to special commandos in other countries, but it pre-dated U.S. and British commando training by nearly a decade. The soldiers of the Waffen-SS were also the first to utilize the camouflage battle dress that was to later become so common. But in one field, that of internal personnel organization, the Waffen-SS has yet to be imitated much less surpassed. The Waffen-SS was probably the most "democratic" armed force in modern times. Rigid formality and class structure between officers and other ranks was strictly forbidden. An officer held down his position only because he had proven himself a better soldier than his men, not because of any rank in society, family connections or superior academic education. In sports -- one of the vital cogs in the Waffen-SS training programs -- officers and men competed as equals in an atmosphere that sponsored team work and mutual respect and reliance. Non-German volunteers of whatever nationality were not regarded as inferiors; they were judged on their ability and performance as soldiers. The idea to actively recruit foreign nationals into the Waffen-SS came shortly after the outcome of the Polish Campaign of 1939, when SS units were being formed and enlarged and it was noticed that a great many men (usually of German extraction) from foreign countries were volunteering for service. The fact that Waffen-SS recruitment among Germans was restricted by the Wehrmacht, made these "out country" volunteers all the more desirable. Since Western Europe contained many sympathizers and admirers of Germany and its National Socialist government, the SS decided to create three new regiments ("Nordland," "Westland" "Nordwest") for Dutch, Flemish, Danish and Norwegian volunteers in the spring of 1940. There was at this time, little in the way of a cohesive, Pan-European ideal to follow, but thousands of recruits turned up anyway, primarily out of disgust for the performances of their respective socialist/pacifist governments. For many there was additional incentive. In Belgium, Holland and France, scores of populist and right-wing political figures had been arrested, incarcerated and beaten, and shot-out-of-hand. The most famous single incident occurred in Abbeville, France in May 1940, when French police lined up 22 leading Belgian right-wing leaders and executed them in a public park shortly before the arrival of the Germans. It was certainly a "war crime" -- one of the first in fact to be committed and documented in World War II -- but try to find it in a history text book! The establishment historians have shied away from any discussion of this event. Following this massacre, many of the followers of the victims flocked to join the new volunteer regiments of the Waffen-SS. The war with the Soviet Union, commencing in June 1941, brought a new direction to the effort to attract European volunteers in what can be called "The Legionary Movement." The Legionary MovementThe "Legionary Movement" was an attempt to attract qualified military personnel from various countries who otherwise would not have considered engagement with the German Armed Forces, by appealing to their national pride and anti-communist convictions. The Waffen-SS undertook the task of forming Legions from "Germanic" countries, while the Wehrmacht, or German Army proper, was given responsibility over Latin and Slavic Legions. The national Legions proved to be a success, but for a number of reasons -- primarily "cost efficiency," redundancy with Waffen-SS elements and size factor -- were not worth perpetuating in the same format. The primary West European Legions were as follows:

Volunteer Legion Flandern: This was initially a 900 man battalion later increased to 1,116 men that served around Lake Ilmen under the 2nd SS Brigade and at times with the 4th SS Police Division and the Spanish "Blue" Division. It acquitted itself splendidly, obtaining mention in the Wehrmacht war bulletin among other honors. Its supreme moment came in March 1943 when it recovered a lost regimental frontline sector from the Soviets in a bold attack and held onto the regained positions for a week against all odds. By the end of the engagement the "Legion Flandern" had been reduced to a net strength of 45 men! Equal numbers of Flemings served with the 5th SS Division "Wiking" and the Volunteer Regiment "Nordwest." Eventually these contingents were merged with new recruits to form the Storm Brigade "Langemarck."

Freikorps Danmark: This was an 1,164 man reinforced battalion that served with considerable distinction in the Demyansk Pocket alongside the 3rd SS Division "Totenkopf." For a time it was let by the swashbuckling Christian Frederick von Schalburg, a Ukrainian-Danish count who met a soldier's death in the frontlines. The "Freikorps" was authorized and fully supported by the government of Denmark. After the war, members of the "Freikorps Danmark" were prosecuted as "traitors" with the Danish government evading responsibility by saying that the volunteers should have known that the government was merely "acting under duress" when it set up the "Freikorps" and signed the Anti-Comintern pact. Later the "Freikorps" formed the nucleus of the 24th SS Regiment "Danmark." [Image: Danish SS Poster.] Finnish Volunteer Battalion of the Waffen-SS: This was a 1,000 man unit that served as a component part of the "Nordland" Regiment of the SS "Wiking" Division. Its greatest moment came in October 1942, when the Finns were able to seize Hill 711 near Malgobek in the south Caucausus in a daring frontal assault. Other German units had repeatedly tried to do the same thing but had failed. The Finns served in the Waffen-SS at the discretion of their government, which in June 1943 thought it would be more discreet to transfer the Battalion from the Waffen-SS to the Finnish Army. The principal Wehrmacht Legions were the following: The French Volunteer Legion Against Communism: It served as the 638th Regiment with the 7th German Infantry Division, participated in the drive on Moscow and fought well whenever it was deployed. It was largely transferred into the Waffen-SS in 1944. Legion Wallonie: This was organized as a mountain-infantry battalion. It was formed by the SS from the French-speaking Belgians (Walloons) and was taken over by the Wehrmacht in late 1941 so as not to offend the "Germanic" Flemings already serving in the Waffen-SS. It fought exceptionally well in the campaign through the Caucausus Mountains alongside the SS Division "Wiking." It contained many former Belgian Army Officers and the famous political leader Leon Degrelle, who exhibited a flare for death-defying heroics. It was finally re-transferred back into the Waffen-SS in June 1943 at Degrelle's request and was reformed as an assault brigade. Croatian Legion: This was a regiment that fought on the southern part of the eastern front with considerable valor and was totally annihilated in Stalingrad. It was later replaced by three full-scale divisions. Spanish Legion: This was the independent 250th Infantry Division of the "Spanish Blue" Division that fought with incredible heroism on the Lake Ilmen Front. After it was withdrawn from the eastern front in August 1943 by Franco, survivors carried on in a Spanish SS Legion that fought until the end of the war. Per Sorensen: Portrait of a LegionaryThe 27 year old Danish Army Lieutenant Per Sorensen (formerly Adjutant of the Viborg Battalion) was the ideal model of what the Germans were looking for when they launched the Legionary Movement. On 1 July 1941, Sorensen volunteered for service with the "Freikorps Danmark" motivated by anti-communist feelings and a vague sort of National Socialist attitude. In the autumn months he attended the Waffen-SS Officer School at Bad Toelz and in the spring of 1942 rejoined the "Freikorps" as commander of the 1st Company.

In the years to come, whether in White Russia or Estonia, Lativia or Pomerania, the troops under Sorensen's command would always do the job. Before every action, the tall, slender Dane would make a personal reconnaisance of the terrain and during the fighting he was always as the hottest spots with a machine-pistol dangling from his neck. To his soldiers, Sorensen had the uncanny habit of attracting the enemy. They passed around the phrase: "Wherever Sorensen is -- the Russians will come!" And they usually were right. For his endless solicitude and patience, he received the nickname "På Sorensen" from his men. Time and time again, Sorensen provided the special qualities so vital in a leader. In January 1944, he took over an entrapped battalion near Vitino in northern Russia and literally led it to safety by staying at the point of the column on a journey through thick, snow shrouded forests. After commanding battalions and battlegroups, Sorensen received command of the 24th SS Regiment "Danmark" just to the east of Berlin in April 1945. Finally, the Regiment was reduced to trying to defend a street-car station in the heart of Berlin. While climbing a telephone pole to try and survey the terrain, Sturmbannführer (Major) Sorensen was picked off by an enemy sniper. On the next day, in the midst of the desperate, last battle for the German capital, Sorensen was given a military funeral in the Ploetzensee cemetery by Germans and Danes from the "Nordland" Division. With shells detonating all around, the body of Sorensen was taken to the cemetery in an armored troop carrier. Over the open grave, Sturmscharführer (Sgt.) Hermann gave a brief eulogy: We are standing here by the graveside to take our last departure from a courageous Danish comrade, the foremost officer and leader of the Regiment "Danmark": Per Sorensen! I must, even in this hour give the thanks of my people for you and your many Danish comrades who have stood so loyally beside us. I would like to express from my heart: may you find peace at last in our bleeding city!As Hermann spoke, the coffin (constructed from ammunition crates by "Nordland" engineers) was lowered into the grave. Two of the Danish officers attending struggled to contain their emotions. Hermann led a last salute and the eight man honor guard fired three salvos over the grave. A woman flak helper tossed flowers into the grave, and each of the Danish and German soldiers attending passed by throwing in a handful of earth. As the great city shook under rumbling artillery fire and great clouds of smoke obscured the sky, the haunting strains of "I had a Comrade" echoed over Sorensen's grave as the funeral reached its conclusion. The tragic symbolism was complete and fitting: in the very heart of Europe, on its last battlefield, a prototypical representative of the European Volunteer Movement had met his end. Continue |