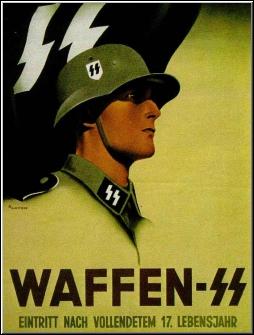

The European Volunteer Movement in World War IIRichard Landwehr |

The European Movement Takes Shape In

1943, the European Volunteer Movement which had been individually developing

in the Legions and the Waffen-SS was finally amalgamated and consecrated

within the ranks of the Waffen-SS. The spiritual citadel of the "Movement"

now became the SS Officers' School at Bad Toelz in Bavaria, which in 1943

established its first "class" (or "inspection") exclusively for West European

Volunteers. Previously the volunteers had received no specialized treatment

but were treated like Germans. Now all of that changed and a sense of European

unity with respect for all nationalities and cultures was openly fostered.

Within the next two years, SS-JS Toelz would produce more than 1,000 highly

motivated European officers from 12 different countries exclusive of Germany. In

1943, the European Volunteer Movement which had been individually developing

in the Legions and the Waffen-SS was finally amalgamated and consecrated

within the ranks of the Waffen-SS. The spiritual citadel of the "Movement"

now became the SS Officers' School at Bad Toelz in Bavaria, which in 1943

established its first "class" (or "inspection") exclusively for West European

Volunteers. Previously the volunteers had received no specialized treatment

but were treated like Germans. Now all of that changed and a sense of European

unity with respect for all nationalities and cultures was openly fostered.

Within the next two years, SS-JS Toelz would produce more than 1,000 highly

motivated European officers from 12 different countries exclusive of Germany.

Bad Toelz was considered the premier officers' training school in World War II and in addition to a thorough training program that featured live ammunition in most field exercises, it offered well-rounded athletic, cultural and educational opportunities. The great opera, musical and theatrical troops of central Europe made frequent visits while the athletic facilities were unsurpassed in Europe. Twelve different coaches, each one either an Olympic or world class champion in his field, supervised a vast sports program that even included golf and tennis. In the academic arena, freedom of speech was not only permitted but encouraged and the writings of such disparate souls as Marx, Hitler, Jefferson and Churchill were openly discussed and debated. What Bad Toelz produced was literally a "Renaissance man" who was also a top-notch military officer. In early 1945, the staff and students were mobilized into the newly authorized 38th SS Division "Nibelungen," and one of the great ironies of the war took place: a mostly German division was officered by non-German Europeans (the officer cadets) instead of the other way around. Once in action against the Americans in southern Bavaria, the Scandinavians, Lowlanders and Frenchmen found themselves opposing an enemy whom they thought could only have existed on the Eastern Front. Like all of the Waffen-SS units to serve in the west in 1945, "Nibelungen" was soon victimized by numerous "war crimes." Entire companies and battalions were bludgeoned and shot to death after going into U.S. captivity. To date this grisly story has only been revealed in bits and pieces and has -- naturally enough -- been largely suppressed by the Allied side. However, it is interesting to note that some former members of the Waffen-SS consider it likely that more of their comrades were killed in American captivity than on the battlefield itself! 1944-45: A European Army at WarThe year 1944 opened with the Flemish SS Storm Brigade "Langemarck" fighting a savage retrograde action near Zhitomir in southern Ukraine. Simultaneously the Scandinavian "Nordland" Division and Dutch "Nederland" Brigade were desperately trying to stem a massive Red Army offensive in the Leningrad sector, and the European "Wiking" Division and Belgian Brigade "Wallonien" were going into the "sack" west of Cherkassy. The breakout from the Cherkassy Pocket on the southern Eastern Front was a true epic of heroism: a sacrificial struggle that bound troops of different nationalities firmly together. In the post-war years the survivors have held annual remembrance meetings so that to this day "Cherkassy" remains a living symbol of the European Voluntary Movement.The spring of 1944 saw the three Baltic SS Divisions fighting with steadfast courage on the eastern boundaries of their countries. In Lithuania, the nucleus for a new SS Division began taking shape under the guidance of former Lithuanian Army generals, but the country was overrun by the communists before the project could be brought to fruition. Against the Anzio beachhead in Italy, the first combat ready Italian SS battalion grimly held its ground against all American breakout attempts. All over Europe, manpower was being voluntarily mobilized into the Waffen-SS to participate in what many people saw as the forthcoming, decisive struggle for the freedom of the continent. The summer of 1944 saw the "battle of the European SS" on the Narva Front in Estonia. Here, nationals from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Flanders, Holland and Estonia shared the trenches and fought shoulder-to-shoulder to throw the Bolsheviks back off "Orphanage Hill" and "Grenadier Hill." Leon Degrelle personally led a battalion from his "Wallonien" Division in a brilliant defensive action near Tartu on the west shore of Lake Peipus. Near Brody in Ukraine, the 14th Ukranian SS Division fought a life-or-death battle to escape from a Soviet encirclement; only about one-fourth of the Division survived the fighting, but they had acquitted themselves well. As the year went on, more and more foreign volunteer divisions were formed. This meant that flexible leadership was needed to handle the different cultural distinctions and surprisingly, the Waffen-SS was equal to the task. Although organized religion was kept separate from the Waffen-SS, volunteers from devout Catholic, Moslem, Greek Catholic and Orthodox countries were given total freedom to practice their religions with their own clergy. For morale purposes, ethnic cultural activities were actively encouraged. It was quite a contrast to the way some minority groups were treated in the Allied armies at the time. Some of the foreign SS divisions composed of Russian and Moslem volunteers had to be disbanded, since the time and personnel needed to develop these units were lacking. By the autumn of 1944 the Waffen-SS European volunteer tally sheet contained the following elements: 2 Dutch brigades, 2 Belgian brigades, 1 French brigade and 1 Italian brigade, (all being transformed into divisions), 2 Croat Moslem divisions, 1 Albanian Moslem division, 2 Hungarian divisions with 2 more in the works that never panned out, 2 Scandinavian/German divisions, 2 Latvian divisions, 1 Estonian division, 2 Russian divisions (both of which would later be transferred to the Vlasov Liberation Army), 1 Ukranian division, 1 Italian/German division, 1 Hungarian/German division, 1 Balkan/German division, 1 Serbian division, numerous ethnic brigades from the Soviet Union, and small detachments of Spaniards, Britons, Greeks, Romanians, Bulgarians, Arabs and Indians. The foreign SS units were all suitably supplied with national badges, insignia and unit distinctions. And while there were many volunteers from such neutral countries as Ireland, Sweden and Switzerland they could not be openly designated as such so as not to offend their respective governments.

In Slovenia and Hungary, the brave Moslems of the 13th SS Division "Handschar" performed well against both Tito's partisans and the Red Army, but in France the 30th White Russian SS Division had virtually collapsed while in action against the Americans and French Maquis. These soldiers had only wished to fight the communists and saw no point in what they were doing in the west. This was not the case in regard to both the 29th Italian SS Division and the 34th Dutch SS Division "Landstorm Nederland." The Italian SS troops fought both the Americans and the rear area communist partisans, and they distinguished themselves as perhaps the best troops that Italy produced during the war. "Landstorm Nederland" first battled the British at Arnhem as part of a hurriedly organized self-defense brigade, but during the winter of 1944-45 it was enlarged into a full-scale 12,000 man infantry division. In the spring of 1945, the almost exclusively Dutch "LN" SS Division gave the British and Canadians fits as they tried with little success to advance into northwest Holland. None of the Allies could figure out why so many Dutchmen chose to join the "Landstorm" Division, so to avoid embarrassment, the story of this unit has been largely suppressed ever since. For the Dutch volunteers, there was no motivation problem. The Allies had joined with the Bolsheviks against not only their homeland but what they perceived to be European civilization as well. Like their fellow countrymen on the Eastern Front, the men of "Landstorm Nederland" fought with a dedicated resolve. The Belgian and French SS Divisions were brought up to strength in the fall of 1944 from among the many refugees that had fled to Germany plus veterans of the war with Russia. In Holland, volunteers flocked to the Waffen-SS recruiting offices like never before and not because they had to. It didn't take a clairvoyant to see that Germany was virtually finished, but still the European volunteers rushed to join the battle. The establishment historians have never been able to understand this phenomenon, perhaps because it involved an abstract concept alien to most of them: conscience. There was a great desire for many people, who had until this point sat out the war, to finally be "true to themselves"; to make the ultimate sacrifice out of loyalty to their beliefs, their homelands and their fellow countrymen who had already done so much. This was Europe's moment of crisis and many young men made the decision to leap into the crucible. It was a manifestation of spiritual honesty.

The end of 1944 saw Leon Degrelle's 28th SS Division "Wallonien" moving into that part of Belgium that had been retaken in the Ardennes offensive, where it received a hearty welcome and new recruits! But the curtain was rising on the last act on the Eastern Front, and in the weeks ahead most of the European volunteer forces would be in action there. In Kurland, Western Latvia three SS divisions -- l1th "Nordland," 23rd "Nederland" and 19th Letvian -- were caught up in an unequal life-or-death struggle in January 1945. A few extracts from the history of the 49th Dutch SS Regiment "De Ruyter" gave the flavor of the action: (From the series of articles titled "Soldiers of Europe: The III. SS Panzer Korps" in Siegrunen Magazine). After a surging, back-and-forth struggle, the south bastion of Ozoli Hill fell irretrievably to the Russians. The over-powered First Co./SS Rgt. "De Ruyter" fell back to the west. Untersturmführer Schluifelder, the commander, was badly wounded and shot himself rather than fall into enemy hands.By the end of the fighting, the SS Regiment "De Ruyter" with a nominal strength of 2,000 men had been reduced to 80 combatants! The Regiment was rebuilt on the run and thrown into action again on the Pomeranian Front less than two weeks later. For the first time "De Ruyter" received a Third Battalion, this being composed of Dutch and German war reporters whose jobs had become rather superfluous given recent military reversals. Remaining in Latvia was the 19th Latvian SS Division, which time and again had proved itself the mainstay of bitter defensive fighting and had received several mentions in the Wehrmacht war bulletins. The Latvian volunteers received more decorations than any other non-German group in the Waffen-SS, including the award of 13 Knight's Crosses, a good indication of their contributions on the battlefield. In Poland and Silesia, the Hungarian and Estonian SS Divisions were temporarily able to stop the enemy onslaught, even though the commander of the 26th SS Division, "Hungaria," Oberführer Zoltan von Pisky had been killed in action at Jarotschin. As the Eastern Front was pushed slowly westwards, bits and pieces of the 27th Flemish SS Division "Langemarck" were rushed to the Oder River line from various training camps. Here they served alongside their co-national rivals, the Walloons, in a spirit of unbridled comradeship. First Battalion of the 66th SS Regiment/Division "Langemarck" picked up the nickname "leaping tiger" for the way its soldiers threw themselves into battle. But even more amazing was the fact that the battalion was composed mostly of teenagers from the Flemish Hitler Youth who had volunteered for service in the Waffen-SS after their country had been overrun by the Allies. If there was one drawback to service in this battalion it was that the regimental quartermaster stubbornly saw that the young troopers received a special ration of Schokolade and Bonbons instead of the schnapps and cigarettes passed out to the older soldiers! With a good sense of historical irony, the Eastern Front slowly bent and folded itself around the German capital city of Berlin, throwing a good many of the foreign volunteers into the battle for the city. Regiments of the 15th Latvian SS Division, battered beyond belief, had naively decided to throw in their lot with the western allies against the communists (which proved to be an unfortunate decision for many of the officers who were forcibly repatriated to the death camps), and made a complete circuit of Berlin travelling in no-man's land all the time, until they saw a chance to make it to the American lines. The Division's reconnaissance battalion went out a little too far on a scout mission and wound up being impressed into the defense of the city. To the north of Berlin, 500 survivors of the 33rd French SS Division "Charlemagne" which had been decimated in the defense of Pomerania, actually volunteered to go to the defense of the German capital, even though the Divisional commander had absolved them from any more service obligations. In the week of the epic battle that followed, these Frenchmen constituted the core of defense in the city center, displaying courage and fortitude on a scale seldom seen. When the fighting was over, only a few dozen would still be alive and four of their number would be decorated with Knight's Cross. One could call their mission a "beau geste," but the French soldiers saw it as a moral obligation -- another abstract concept the establishment scholars choke on. The following is a description of these soldiers from the aritlce "Defeat in the Ruins: France's Last Battle for Europe," by Gustav Juergens (Siegrunen, June 1980): By this time, the warriors of the "Charlemagne" Division didn't even look like human beings any more. Their eyes were burning and their faces skull-like and covered in dirt and mortar dust. Supplies only came in negligible amounts, the most telling being the lack of water. The young SS men moved like robots through the hell of Berlin. The future was the farthest thing from anyone's mind. The only motivating idea that burned in their consciousness and kept them from collapsing was their flaming desire to come to grips with the Bolsheviks! They had to throw hand grenades, destroy tanks, and hold out against the Reds. That was their only reason for living and for dying.The SS Divisions "Wallonien," "Nederland" and "Nordland after spearheading the last successful offensive on the Vistula sector to relieve the trapped garrisons at Arneswalde, had been driven inexorably westward. "Nederland" was split into two segments, one being trapped and destroyed in the Halbe Pocket to the south of Berlin and the other retreating to the north of Berlin. Much of the "Nordland" Division, including the staff elements, wound up in Berlin itself. At Prenzlau, due north of Berlin, the Flemish "Langemarck" Division led by the "leaping tigers" of its Hitler Youth battalion, made the last relief attack against the communist encirclement on 25 April 1945. In violent, savage fighting "Langmarck" was burnt to a cinder along with the "Wallonien" Division and parts of "Charlemagne" and "Nordland"; the survivors were forced to fall back towards the Elbe River. In Silesia, the 20th Estonian SS Division was surrounded and forced to surrender to the Soviets; beginning what for most, would be a long, final journey to the Gulags. On the Austrian frontier, the Ukrainian, Moslem and Cossack SS formations fought with skill and valor before retreating to the west. Most of the Moslems and Cossacks would later be forcibly repatriated to their deaths at the hands of the Yugoslav and Soviet communists; the Ukrainians escaped this real "holocaust" by posing as pre-war Polish citizens. Going with the Cossacks of 15th SS Army Corps to the Gulags, was their beloved commander, Gen. Lt. Helmuth von Pannwitz, the first foreign national ever to be freely elected Ataman of the Cossack tribes. He chose to share the fate of his men although he could have gone into comfortable Allied internment. In 1947, von Pannwitz, along with the Cossack leaders of the 15th SS Corps, was hanged in Moscow as a "war criminal"; the Cossack soldiers and about one-half million others of their nationality were physically exterminated with the assistance of the United States and Great Britain. In Italy, after putting up a brave fight, the 29th Italian SS Division surrendered either to the Americans or to the Red partisans and almost to a man, the Italian SS men were put to death. Between 20,000-30,000 of these volunteers were therefore killed outright in captivity. In Yugoslavia another great nightmare unfolded. 10,000 Moslem volunteers from the 13th SS Division "Handschar" were exterminated in a mass execution and their bodies stuffed in an abandoned mine shaft. Many of the soldiers of the 7th SS Mountain Division "Prinz Eugen," recruited from Yugoslav Germans, met a similar fate. In Kurland, Latvia, where a small German Army Group had courageously held out against vastly superior enemy forces until the end of the war, 14,000 members of the 19th Latvian SS Division marched into captivity and oblivion-they were never heard from again. In Berlin, members of the Spanish SS Legion attempted to breakout of the city wearing pilfered Red Army uniforms; none made it. Those caught by the communists were shot as spies and those intercepted by the Germans were shot as turncoats. When General Krebs went to surrender the Berlin garrison early on the morning of 1 May 1945, he took with him the Latvian Waffen-Obersturmführer (1st Lt.) Nielands as an interpreter. After performing his duty, Nielands returned to the command of his 80 man company from the 15th SS Recce Battalion. For the Latvians there would be no surrender -- they asked for no quarter from the Soviets and they gave none themselves. In the ruins of the Air Ministry building the Latvian SS troops made their last stand. In hand-to-hand combat they fought to the death. A few of the volunteers trapped in Berlin actually escaped. The Danish Obersturmführer Birkedahl-Hansen, suffering from jaundice, led some men from Regiment "Danmark" successfully out of the city through Spandau to the northwest. They made their way to the seaport of WarnemiInde and took a row boat back to Denmark, thus escaping a long trek to Siberia. The end of the war saw most of the European volunteers frantically trying to make it to the western Allied lines. Surrender, though, only marked the beginning of their problems. The "democratic" governments of the "liberated" countries were determined to inact a painful vengeance. In each country some of the more prominent volunteers were run through quick "judicial" proceedings and executed, with the others being stripped of their civil rights and sentenced to prison terms of varying lengths. Those that wound up in Soviet hands were either: 1) extradited to their home countries for criminal proceedings or 2) simply shipped to forced labor camps with the Germans. Those that survived up to a decade or so of this treatment were eventually sent home. The final tally sheet for the European Volunteer Movement ran roughly as follows: (Waffen-SS only) Western Europe: 162,000 volunteers, ranging from about 55,000 in Holland to 80 from Liechtenstein. Out of this total about 50,000 were killed or missing. Included in this figure would be 16,000 Dutchmen and 11,500 Belgians.In some countries like Holland, the "volunteer" problem was so great that censorship was imposed, which in most cases remains in place to this day. The Dutch were particularly brutal in treating their military "collaborators"; incarcerating many for long terms in concentration camps that followed the German models faithfully. Many volunteers in the Netherlands subsequently rose to prominence in the political and business fields, but because of their "background" remained vulnerable to a form of blackmail that has seen some of them (including parliamentary leaders) sent into distant oblivion. Treatment of returning volunteers was equally harsh in other countries. Belgium executed many both legally and illegally while keeping a majority of their "military collaborators" locked up in concentration camps run in the German style. In France, some of the more prominent officers were executed, while the rank-and-file of the "Charlemagne" Division was given the option of doing time in Indo-China with the Foreign Legion. Joining them were numerous Hungarian and German SS men who had wound up in French captivity.

When the volunteers were mentioned at all after the war, it was always in a very derogatory manner; they were usually referred to as criminals and mercenaries. The Dutch went so far as to hire a psychiatrist to buttress this theory. He interviewed 400 volunteers and later propounded the thesis that these men had not served out of any moral committment but had "sold their souls" for material inducements and adventure. This has been pretty much the establishment line ever since, although it is never mentioned that the volunteers interviewed (constituting one-half of one percent of the total number of Danish military collaborators), were quite willing to say anything to secure release from their concentration camp. If one looks at the rigorous screening process that the Germans applied to their foreign volunteers the myth of their being "criminals" and "mercenaries" is pretty well exploded. The basic criteria for acceptance in the Waffen-SS revolved around the applicant's physical fitness, mental attitude and past record. Anyone with a criminal record was simply not accepted, although some did slip through. Utilizing these standards, the Waffen-SS accepted only 3,000 recruits out of about 12,000 who flooded the recruiting offices of the original Dutch Legion. And out of this 3,000 another 400 would be culled out during training for either harboring a criminal past or an incompatible political attitude. Similarly we can look at the Ukranian volunteers and see that out of 81,999 initial applicants only 29,124 were finally accepted after screening! If there is any judgement that can be made from this it is that the men who got into the Waffen-SS usually represented the best human material that their respective countries had to offer. There is no way to categorize them individually since they came from all different classes and backgrounds sharing only one common denominator: a love of their country and continent. Continue |