Mythology and Religion of the HindoosAlexander Murray |

| In the Sanscrit language the myths

common to the Aryan nations are presented in, perhaps, their simplest form.

Hence the special value of Hindoo myths in a study of Comparative Mythology.

But it would be an error to suppose that the myths of the Greeks, Latins,

Slavonians, Norsemen, old Germans, and Celts were derived from those of

the Hindoos. For the myths, like the languages, of all these various races,

of the Hindoos included, are derived from one common source. Greek, Latin,

Sanscrit, etc., are but modifications of a primitive Aryan language that

was spoken by the early "Aryans" before they branched away from their original

home in Central Asia, to form new nationalities in India, Greece, Northern

Europe, Central Europe, etc.

The Sanscrit language is thus not the mother, but the elder sister of Greek and the kindred tongues: and Sanscrit or Hindoo mythology is, in like manner, only the elder sister of the other Aryan mythologies. It is by reason of the discovery of this common origin of these languages that scholars have been enabled to treat mythology scientifically. For example, many names unintelligible in Greek are at once explained by the meaning of their Sanscrit equivalents. Thus, the name of the chief Greek god, Zeus, conveys no meaning in itself. But the Greek sky-god Zeus evidently corresponds to the Hindoo sky-god Dyaus, and this word is derived from a root dyu meaning "to shine." Zeus then, the Greek theos, and the Latin deus, meant originally "the glistening ether." Similarly other Greek names are explained by their counterparts, or cognate words in Sanscrit. Thus the name of Zeus's wife, Hera, belongs to a Sanscrit root svar, and originally meant the bright sky: the goddess herself being primarily the bright air. Athene is referred to Sanscrit names meaning the light of dawn, and Erinys is explained by the Sanscrit Saranyn. In the Hindoo Pantheon there are

two great classes of gods -- the Vedic and the Brahmanic. The Vedic gods

belong to the very earliest times, appear obviously as elemental powers,

and are such as would have been worshipped by a simple, uninstructed, agricultural

people. The Brahmanic religion was, in great part at least, a refined development

of the former; and was gradually displacing the simpler worship of Vedism

as early as fifteen centuries or more before the birth of Christ. Five

or six centuries before the last event, Dissent, under the name and form

of Buddhism, became the chief religion of India; but in about ten centuries

Brahmanism recovered its old position. Buddhism now retains but comparatively

few followers in India. Its chief holds are in Burmah, Siam, Japan, Thibet,

Nepaul, China, and Mongolia: and its followers, in the present day, perhaps

outnumber those of all other religions put together.

THE VEDIC GODSDYAUS was, as we have already indicated, the god of the bright sky, his name being connected with that of Zeus through the root dyu. As such Dyaus was the Hindoo rain-god, i.e., primarily, the sky from which the rain fell. That the god-name and the sky-name were thus interchangeable is evident from such classical expressions as that "Zeus rains" (i.e., the sky rains), and meaning a damp atmosphere. In such expressions there is hardly any mythological suggestion: and the meaning of the name Dyaus, -- like those of the names Ouranos and Kronos in Greek, -- always remained too transparent for it to become the nucleus of a myth. Dyaus, however, was occasionally spoken of as an overruling spirit. The epithet, Dyaus pitar, is simply Zeus pater -- Zeus the father; or, as it is spelled in Latin, Jupiter. Another of his names, Janita, is the Sanscrit for genetor, a title of Zeus as the father or producer. Dyaus finally gave place to his son Indra.VARUNA is also a sky-god: according to another account, a water-god. The name is derived from Var, to cover, or to overarch: and so far Varuna means the vault of heaven. Here, then, we seem to find a clue to the meaning of the Greek Ouranos, whom we already know to have been a sky-god: Ouranos means the coverer, but, as observed above, the name would have remained unintelligible apart from its reference to the Sanscrit name. The myth of Varuna is a wonderful instance of the readiness and completeness with which the Hindoo genius spiritualized its sense impressions. From the conception of air (or breath), the thousand-eyed (or starred) Varuna who overlooked all men and things, the Indian Aryans passed to the loftier conception of Varuna as an all-seeing god or providence, whose spies, or angels, saw all that took place. Some of the finest passages in the Vedic hymns are those in which the all-seeing Varuna is addressed: as in the following verses -- the second of which is so remarkable for its pathetic beauty -- from Müller's "Rigveda": This complete transition from the physical to the spiritual, this abstract or contemplative bias of the Hindoo mind, is curiously instanced in the name Aditi. Originally it meant the illimitable space of sky beyond the far east, whence the bright light gods sprang. Then Aditi became a name for the mother in whose lap the gods were nursed; and finally, it seems a name for the incomprehensible and Infinite and Absolute of the metaphysicians. INDRA The connection, or identity, between Zeus and Dyaus seems to be chiefly a philological one. There is a greater resemblance between Indra and Zeus than between Zeus and Dyaus. Indra, as the hurler of the thunderbolts, and as a "cloud compeller," coincides with Zeus and Thor. The myth of Indra -- the favourite Vedic god -- is a further instance of that transition from the physical to spiritual meaning to which we have referred; though Indra is by no means so spiritual a being as Varuna. It is also a good instance of the fact that, as the comparative mythologists express it, the further back the myths are traced the more "atmospheric" do the gods become. First, of the merely physical Indra. His name is derived from indu, drop-sap. He is thus the god of rain. The name parjanya means rain-bringer. Indra shatters the cloud with his bolt, and releases the imprisoned waters. His purely physical origin is further indicated by the mythical expression that the clouds moved in Indra as the winds in Dyaus -- an expression implying that Indra was a name for the sky. Also, the stories told of him correspond closely with some in classical mythology. Like Hermes and Herakles, he was endowed with precocious strength; like Hermes he goes in search of the cattle, the clouds which the evil powers have driven away ; and like Hermes he is assisted by the breezes -- though in the Hindoo myth by the storms rather--the Maruts, or the crushers. His beard of lightning is the red beard of Thor. In a land with the climatic conditions of India, and among an agricultural people, it was but natural that the god whose fertilizing showers brought the corn and wine to maturity should be regarded as the greatest of all. He who as soon as born is the first of the deities, who has done honour to the gods by his exploits; he at whose might heaven and earth are alarmed, and who is known by the greatness of his strength: he, men, is Indra.The first verse in the preceding hymn from the "Rigveda" perhaps refers to Indra as a sun-god, and to the rapidity with which, in tropical climates, the newly-born sun grows in heat-giving powers. The Abi, or throttling snakes, of the third verse, is the same as the Greek Echidna, or the Hindoo Vritra; and is multiplied in the Rakhshasas -- or powers of darkness -- against which the sky-god Indra wages deadly war. He is likewise spoken of in the same hymn in much the same kind of language that would naturally be applied to the creator and sustainer of the world. But so is almost every Hindoo deity. Absolute supremacy was attributed to each and every god whenever it came to his turn to be praised or propitiated. SURYA corresponds to the Greek

Helios. That is, he was not so much the god of light as the special god

who dwelt in the body of the sun. The same distinction exists between Poseidon

and Nereus; the one being the god of all waters, and even a visitor at

Olyrnpos, the other a dweller in the sea. Surya is described as the husband

of the dawn, and also as her son.

SAVITAR is another personification of the sun. His name means the "Inspirer," and is derived from the root sa, to drive or stimulate. As the sun-god he is spoken of as the golden-eyed, golden-tongued, and golden-handed; and if we suppose that in process of time those epithets -- quite appropriate in a purely physical sense -- came to lose their purely physical meaning, so that Savitar came to signify an actual person who possessed a hand made of real gold, it is evident that the priests and others must have exercised their ingenuity in trying to account for the fact. Thus the Hindoo commentators say that Savitar cut off his hand at a sacrifice, and that the priests gave him a golden one instead. Savitar thus corresponds to the Teutonic god Tyr, whose hand was cat off by the wolf Fenris. Like other gods in the Hindoo and Norse mythologies, Savitar is regarded as all-powerful. That Savitar is a sun-god appears from the following passages from the "Rigveda":-- Shining forth he rises from the lap of the dawn, praised by singers; he, he, my god Savitar, stepped forth, who never misses the same place.The second passage seems to identify Savitar with Odin, who was also "the wanderer " -- Wegtam, and who was one-eyed, as Savitar was one-handed. SOMA In some respects the myth of Soma is the most curious of any. Soma, as the intoxicating juice of the Soma plant, corresponds to that mixture of honey and blood of the Qoasir [Kvasir], which, in the Norse mythology, imparts prolonged life to the gods. In the Rigveda the Soma is similarly described; as also the process by which it is converted into an intoxicating liquid. But in the same hymns Soma is also described as an all-powerful god. It is he who gives strength to Indra, and enables him to conquer his enemy Vritra, the snake of darkness. He is further, like Vishnu, Indra, and Varuna, the supporter of heaven and earth, and of gods and men; thus it would seem as if the myth of the god Soma is but an instance of that fetishistic stage in the history of the human kind during which men attributed conscious life and energy to whatever hurt or benefited them. The following passages from the "Rigveda" are adduced to show in what terms Soma was spoken of as a god, and as a mere plant:-- And again-- In filter, which is the support of the world, thou, pure Soma, art purified for the gods. The Usijas first gathered thee. In thee all their worlds are contained.

As another curious instance of

the sort of fetishism to which we have referred, there is a Vedic description

of Agni as being generated from the rubbing of sticks, after which he burst

forth from the wood like a fleet courser. Again, when excited by the wind

he rushes amongst the trees like a bull, and consumes the forest as a raja

destroys his enemies. Such sentiments of course prove the purely physical

origin of the god Agni; and it is hardly necessary to observe that, like

Indra., Varuna, Soma, Vishnu, etc., he is an all-powerful god, and supporter

of the universe.

VAYU is the god of the winds, or

of the air. Allied to him are the Maruts, -- the storm-gods, or " crushers,"

whose name is derived from a root meaning to grind, and is obviously connected

with such names as Mars and Ares. The same root appears in Miolnir, an

epithet of Thor, conceived as the crashing, or crushing god. The Maruts

are the Hindoo counterparts of the Norse Ogres -- the fierce storm-beings

who toss the sea into foam, and who, in the Norse Tales, are represented

as being armed with iron clubs, at every stroke of which they send the

earth flying so many yards into the air. The primary meaning of the name

is clear from the Vedic passages which describe the Maruts as roaring among

the forest trees, and tearing up the clouds for rain.

USHAS Of all the personifications of Hindoo mythology, by far the purest and most touching and beautiful is Ushas, whose name is the same as the Greek Eos -- or the Dawn. The name Ushas is derived from a root us, to burn. She is also the same as the Sanscrit Ahoma, or Dahana, and the Greek Athene, and Daphne. The language in which the physical Ushas was spoken of was especially capable of easy transformation into a purely spiritual meaning. The dawn-light is beautiful to all men, barbarous or civilized; and it did not require any great stretch of poetic fancy to represent Ushas as a young wife awakening her children, and giving them new strength for the toils of the new day. It happens that the word which, in Sanscrit, means " to awake," also means "to know"; and thus, like the Greek Athene, Ushas became a goddess of wisdom. The following passages show how Ushas was regarded by the Vedic worshippers. Ushas, daughter of heaven, dawn upon us with riches; diffuser of light, dawn upon us with abundant food; beautiful goddess, dawn upon us with wealth of cattle.Had we space for discussion of so interesting a subject, it would be easy to show how naturaliy the language in which the Vedic gods are described must ultimately have suggested a monotheistic conception. Meantime we content ourselves with the following monotheistic hymn, translated by Dr. Max Müller. In the beginning there rose the source of golden light. He was the only lord of all that is; he established this earth and this sky: who is the god to whom we shall offer our sacrifice? THE BRAHMANIC GODS Of

the later Hindoo religion the chief deities are Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva

-- forming the Hindoo Trinity, or Trimurti. These gods, however, are not

regarded as separate, independent gods, but merely as three manifestations

or revelations or phases of the spirit or energy of the supreme incomprehensible

being Brahm. That the trinity is a comparatively late formation appears

from the fact that it was unknown to the commentator Yaska. Yaska's trinity

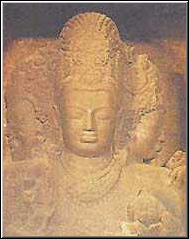

is composed of the three Vedic gods -- Agni, Vayu, and Surya. [Image: Bust

of Trimurti ("having three forms") in the caves at Elephanta. Trimurti's

three faces on a single body represent the creative (Brahma), preservative

(Vishnu) and destructive (Shiva) aspects of the Supreme Being.] Of

the later Hindoo religion the chief deities are Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva

-- forming the Hindoo Trinity, or Trimurti. These gods, however, are not

regarded as separate, independent gods, but merely as three manifestations

or revelations or phases of the spirit or energy of the supreme incomprehensible

being Brahm. That the trinity is a comparatively late formation appears

from the fact that it was unknown to the commentator Yaska. Yaska's trinity

is composed of the three Vedic gods -- Agni, Vayu, and Surya. [Image: Bust

of Trimurti ("having three forms") in the caves at Elephanta. Trimurti's

three faces on a single body represent the creative (Brahma), preservative

(Vishnu) and destructive (Shiva) aspects of the Supreme Being.]

Agni, in such trinity as the Brahmanic,

appears to be known in the Mahabharata, which represents Brahma, Vishnu,

and Indra as being the sons of Mahadeva, or Shiva. Perhaps, however, the

reason of this is to be found in the mutual jealousy of the two great sects,

Vaishnavas and Saivas, into which the Hindoo religion came to be divided.

To Brahm as the self-existent -- of whom there is no image -- there existed

neither temples nor altars. As signifying, among other things, impersonality,

the name Brahm is of the neuter gender, and the divine essence is described

as that which illumines all, delights all, whence all proceeds, that of

which they live when born, and that to which all must return.

BRAHMA is that member of the triad whose name is most familiar to Englishmen, and best familiar to the Hindoos themselves. Images of him are found in the temples of other gods, but he has neither temples nor altars of his own. The reason of this is that Brahma, as the creative energy, is quiescent, and will remain so until the end of the present age of the world -- of the Kali Yuga, that is -- only a small portion of whose 432,000 years has already passed.

Brahma is figured as a four-headed god, bearing in one hand a copy of the Vedas, in another a spoon for pouring out the lustral water contained in a vessel which he holds in a third hand, while the fourth hand holds a rosary. The rosary was used by the Hindoos to aid them in contemplation, a bead being dropped on the silent pronunciation of each name of the god, while the devotee mused on the attribute signified by the name. [Image: Four-headed Brahma.] Brahma, like each god, had his

sacti,

or wife, or female counterpart, and his vahan, or vehicle, whereon

he rode. Brahma's sacti is Saraswati, the goddess of poetry, wisdom,

eloquence, and fine art. His vahan was the, goose --

hanasa, in

Latin, gans.

VISHNU is the personification of the preserving power of the divine spirit. The Vaishnavas allege that Vishnu is the paramount god, because there is no distinction in the sense of annihilation, but only change or preservation. But of course the argument would cut all three ways, for it might as well be said that creation, preservation, and destruction are at bottom only one and the same thing -- a fact thus pointing to the unity of God. Of the two Hindoo sects the Vaishnaivas are perhaps the more numerous.

SHIVA is the destroyer -- the third phase of Brahm's energy. He is represented as of a white colour. His sacti is Bhavani or Pracriti, the terrible Doorga or Kali, and his vahan a white bull. Sometimes Shiva is figured with a trident in one hand. and in another a rope or pasha, with which he, or his wife Kali, strangles evil-doers. His necklace is made of human skulls; serpents are his earrings; his loins are wrapped in tiger's skin; and from his head the sacred river Ganga is represented as springing. Among the minor deities may be

mentioned Kuvera, the god of worth; Lakshmi being the goddess of wealth;

Kama-deva ,the god of love, who is represented as riding on a dove, and

armed with an arrow of flowers, and a bow whose string is formed of bees

; and thirdly, Ganesa, the son of Shiva and Prithivi, who is regarded as

the wisest of all the gods, is especially the god of prudence and policy,

and is invoked at the opening of Hindoo literary works.

AVATARS OF VISHNU The word Avatar means, in its evident sense, Descent -- that from the world of the gods to the world of men. In these descents, or incarnations, the purpose of Vishnu has always been a beneficent one. His first avatar is named Matsya, wherein, during the reign of King Satyavrate, Vishnu appeared in the form of a fish. For the world had been deluged by water for its wickedness, and its inhabitants, except the king and seven sages, with their families, who, together with pairs of all species of animals entered into an ark prepared for them, and of which the fish took care, by having its cable tied to its horn. In the second, or Kurma avatar, Vishnu appeared in the form of a tortoise, supporting Mount Mandara on his back, while the gods churned the sea for the divine ambrosia. In the Varaha, or third avatar, Vishnu appeared as a boar to save the earth when it had been drowsed a second time. The boar went into the sea and fished the earth out on his tusks. In the fourth he appeared as Narasingha, the man-lion, to free the world from a monarch who, for his austerities, had been endowed by the gods with universal dominion. In this shape Vishnu tore the king to pieces. Subsequently he appeared as a dwarf; then as Rama, the hero of the Ramayana, who likewise was a beneficent being. His chief incarnation appears in Krishna, the god who is most loved by the Hindoos. Buddha, the founder of the Buddhist religion, was also said to be an incarnation of Vishnu. Nine of these avatars have already passed. In the tenth, or Kalki Avatara, he will appear armed with a scimitar, and riding on a white horse, when he will end the present age; after which he will sleep on the waters, produce Brahma, and so inaugurate a new world.

Alexander Murray, Manual of Mythology (London, 1874), 326-40. |

|

|