Intellectual TerrorismDr. Tomislav Sunic |

The

modern thought police is hard to spot, as it often seeks cover under soothing

words such as "democracy" and "human rights." While each member state of

the European Union likes to show off the beauties of its constitutional

paragraph, seldom does it attempt to talk about the ambiguities of its

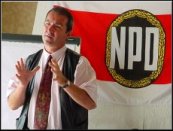

criminal code. [Image: Croatian academic Tomislav Sunic at a meeting of

the NPD, Germany's leading nationalist party.] The

modern thought police is hard to spot, as it often seeks cover under soothing

words such as "democracy" and "human rights." While each member state of

the European Union likes to show off the beauties of its constitutional

paragraph, seldom does it attempt to talk about the ambiguities of its

criminal code. [Image: Croatian academic Tomislav Sunic at a meeting of

the NPD, Germany's leading nationalist party.]

In June and November, 2002, the European Commission held poorly publicized meetings in Brussels and Strasbourg whose historical importance regarding the future of free speech could overshadow the recent launching of the new euro currency. At issue is the enactment of new European legislation whose objective is to counter the growing suspicion about the viability of the multiracial European Union. Following the events of September 11, 2001, and in the wake of certain veiled anti-Israeli comments in some American and European journals, the European Commission is aiming to exercise maximum damage control, via maximum thought control. If the new bill on "hate crime" sponsored by the Commission passes through the European parliament and is applied by the EU Council of Ministers, the judiciary of any individual EU member state in which this alleged "verbal offense" has been committed will no longer carry legal weight. Legal proceedings and "appropriate" punishment will become the prerequisite of the European Union's supra-national courts. When the law is adopted, it will automatically become law in all European Union member states, from Greece to Belgium, from Denmark to Portugal. Pursuant to the law's ambiguous wording of the concept of "hate crime" or "racial incitement," anyone convicted of such an ill-defined verbal offense in country "A" of the European Union can be fined or imprisoned in country "B" of the European Union. (In reality, this is already the case.) The enactment of this EU law would be reminiscent of the reenactment of the communist criminal code of the late Soviet Union. The communist judiciary of the now-defunct communist Yugoslavia had for decades resorted to similar legal meta-language, such as the paragraph on "hostile propaganda" of its criminal code, Article 133. Such semantic abstraction could apply to any suspect -- regardless of whether the suspect committed acts of physical violence against the communist state or simply cracked a joke critical of communism.

Since 1994, Germany, Canada, and Australia have strengthened their laws against dissenting views, particularly against historical revisionists and nationalists. Several hundred German citizens, including a number of high-profile scholars, have been accused of inciting racial hatred or denying the Jewish Holocaust, on the basis of the strange legal neologism contained in Article 130 of the German Criminal Code -- Volksverhetzung, a linguistic barbarism literally meaning "incitement to popular resentments," or, more freely, "goading the people." On the basis of that poorly conceived yet overarching grammatical construct, it is now easy to place any journalist or professor in legal difficulty if he questions the writing of modern history or the rising number of non-European immigrants. In England and America the legal tradition presupposes that everything not explicitly forbidden is allowed. By way of contrast, in Germany a legal tradition of long standing presupposes that everything not explicitly allowed is forbidden. That difference may underlie Germany's adoption of stringent laws against alleged or real Holocaust denial. In December 2002, during a visit to Germany, Jewish-American historian Norman Finkelstein called upon the German political class to cease being a victim of "Holocaust industry" pressure groups. He remarked that such a reckless German attitude only provokes hidden anti-Semitic sentiments. As was to be expected, nobody reacted to Finkelstein's remarks, for fear of being labeled anti-Semitic themselves. Instead, the German government agreed last year to pay, courtesy of its taxpayers, a further share of 5 billion euros for the current fiscal year to some 800,000 Holocaust survivors. Such silence is the price paid for intellectual censorship in democracies. When discussion of certain topics is forbidden, the climate of frustration starts growing, followed by individual terrorist violence. Can any Western nation that inhibits the free expression of diverse political views -- however aberrant they may be -- call itself a democracy? Although America prides itself on its First Amendment, free speech in higher education and the media is subject to didactic self-censorship. Expression of politically incorrect opinions can ruin the careers or hurt the grades of those naive enough to rely on their First Amendment rights. Among tenured professors in the United States it is becoming more common to give passing grades to many minority students in order to avoid legal troubles with their peers, at best, or to avoid losing their job, at worst. In a similar vein, according to the Fabius-Gayssot law, proposed by a French Communist deputy and adopted in 1990, a person publicly uttering doubts about modern antifascist victimology risks serious fines or imprisonment in France. A number of writers and journalists in France and Germany have committed suicide, lost their jobs, or asked for political asylum in Syria, Sweden, or America. Similar repressive measures have recently been enacted by multicultural Australia, Canada, and Belgium. Many East European nationalist politicians, particularly from Croatia, wishing to visit their expatriate countrymen in Canada or Australia, are denied visas by those countries on the grounds of their alleged extremist nationalistic views. For the time being, Russia and other post-communist countries are not subject to the repressive thought control that exists in the United States or the European Union. Yet, in view of the increasing pressure from Brussels and Washington, that may change. Contrary to widespread beliefs, state terror, i.e., totalitarianism, is not only a product of violent ideology espoused by a handful of thugs. Civic fear, feigned self-abnegation, and intellectual abdication create the ideal ground for the totalitarian temptation. Intellectual terrorism is fueled by a popular belief that somehow things will straighten out by themselves. Growing social apathy and rising academic self-censorship only boost the spirit of totalitarianism. Essentially, the spirit of totalitarianism is the absence of all spirit.

Dr. Tomislav Sunic is a distinguished advocate of the European New Right. In one of his most recent appearances in the United States, he spoke on "Third World Immigration: A Threat to Europe and Lessons for America" at an event sponsored by the New York chapter of the Council of Conservative Citizens. |

|

|