The Way of Absolute DetachmentSavitri Devi |

I

spent that day and the next, and the rest of the week, meditating upon

the way of absolute detachment which is the way of the strong, in the light

of the oldest known summary of Aryan philosophy -- the Bhagavad-Gîta

-- and in the light of all I knew of the modern Ideology for the love of

which I was in jail. And more I thus meditated, more I marveled at the

accuracy of the statement of that fifteen year-old illiterate Hindu lad

who had told me, in glorious '40': "Memsaheb [Hindi for "White lady"],

I too admire your Führer. He is fighting in order to replace, in the

whole West, the Bible by the Bhagavad-Gîta." "Yes," thought

I, "to replace the equalitarian and pacifist philosophy of the Christians

by the philosophy of natural hierarchy and the religion of detached violence

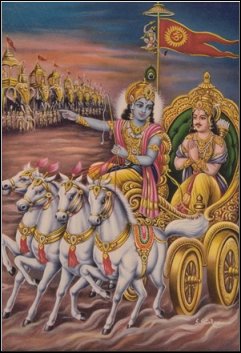

-- the immemorial Aryan wisdom!" [Image: Krishna and Arjuna observe the

armies on the Battlefield of Kurukshetra, the Field of Justice.] I

spent that day and the next, and the rest of the week, meditating upon

the way of absolute detachment which is the way of the strong, in the light

of the oldest known summary of Aryan philosophy -- the Bhagavad-Gîta

-- and in the light of all I knew of the modern Ideology for the love of

which I was in jail. And more I thus meditated, more I marveled at the

accuracy of the statement of that fifteen year-old illiterate Hindu lad

who had told me, in glorious '40': "Memsaheb [Hindi for "White lady"],

I too admire your Führer. He is fighting in order to replace, in the

whole West, the Bible by the Bhagavad-Gîta." "Yes," thought

I, "to replace the equalitarian and pacifist philosophy of the Christians

by the philosophy of natural hierarchy and the religion of detached violence

-- the immemorial Aryan wisdom!" [Image: Krishna and Arjuna observe the

armies on the Battlefield of Kurukshetra, the Field of Justice.]

I recalled in my mind verses of the old Sanskrit Scripture -- words of Krishna, the God incarnate, to the Aryan warrior Arjuna: "As the ignorant act from attachment to action, O Son of Bharata [India], so should the wise act without attachment, desiring only the welfare of the world" (Bhagavad-Gîta, III, verse 25).And I thought: "All is permissible to him who acts for the cause of truth in a spirit of perfect detachment -- without hope of personal satisfaction, without any desire but that of dutiful service. But the same action becomes censurable when performed for personal ends, or even when the one who performs it mingles some personal passion with his or her zeal for the sacred cause. That is also our spirit." I pondered over that one-pointedness, that absolute freedom from petty interests and personal ties that characterizes the real National Socialist. I remembered the story a comrade had once related to me about a man who had had a family of Jews sent to some concentration camp in order to settle himself in their comfortable six-room flat, which he had been coveting for a long time. "He was wrong," my comrade had stated (and his words rang clearly in my memory); "he was not wrong to report those Jews, of course -- that was his duty as a German -- but he was wrong to think at all about the flat; wrong to allow the lust of personal gain to urge him in the least to accomplish his duty. He should have had the Yids packed off, by all means, but simply because they were Yids, because it was his duty, and without caring which German family -- his or someone else's -- occupied the six rooms." "He acted as many average human beings would have acted in his place, had I answered, not exactly to excuse the man, but to say something in his favor, for after all, he was one of us. And I remembered how my comrade had flared up saying: "That is precisely why I blame him! One has no business to call one's self a National Socialist if one acts for the self-same motives as 'average human beings.' One of us should act for the cause alone -- in the interest of the whole nation -- never for himself." "... without attachment, desiring only the welfare of the world." thought I once more, recalling the words of the Bhagavad-Gîta in connection with that statement of a man who had never read it, but who lived according to its spirit, like all those who, today, share in earnest the Hitler faith "The interest of the nation, when that nation is the militant vanguard of Aryan humanity, and the champion of the eternal Aryan ideals, is 'the welfare of the world.'" And I thought, also: "Violence -- not 'non-violence'; but violence with detachment; action -- not inaction, not flight from responsibility, not escape from life; but action freed from selfishness, from greed, from all personal passions; that rule of conduct laid down for all times by the divine Prince of Warriors, upon the Kurukshetra Field, for the true Aryan warriors of all lands, that is our rule of conduct -- our violence; our action. In fact, the true Aryan warrior of today, the perfect Nazi, is a man without passion; a cool-minded, far-sighted, selfless man, as strong as steel, as pure (physically and morally) as pure gold; a man who will always put the interest of the Aryan cause -- which is the ultimate interest of the world -- before everything, even before his own limitless love of it; a man who would never sacrifice higher expediency to anything, not even to the delight of spectacular revenge." I asked myself: "How far have I gone along that path of absolute detachment, which is ours? A German woman who has struggled and suffered for the cause has done me the honor to consider me as 'a genuine National Socialist.' How far do I deserve that honor in the light of our eternal standards of virtue?"

But I then said to myself: "And what if those who watch and wait for our Day in the full knowledge of factors of which I know nothing; what if those who are preparing in silence the resurrection of National Socialist Germany, consider it expedient for us to ally ourselves, one day, for the time being, with this or that side of the now divided enemy camp? What if I had to renounce revenge, to give up the pleasure of mocking, of insulting, of humiliating at least one fraction of our enemies, in the ultimate interest of the Nazi renaissance?" I realized that no greater sacrifice could be asked of me. Yet I answered in my heart: "I would! Yes. I would keep quiet, if that were necessary. I would even praise 'our great allies' of the East or of the West, publicly if I were ordered to; praise them, while hating them, for the sake of highest expediency. I would -- in the interest of Hitler's people; in the interest of regenerate Aryandom: in the interest of the world ordained anew according to the true natural hierarchy of races and individuals; in the interest of the eternal truth which Adolf Hitler came to proclaim anew in this world." I remembered more words of Krishna, the God incarnate, upon the Kurukshetra Field: "Whenever justice is crushed; whenever evil rules supreme, I Myself, come forth. For the protection of the righteous, for the destruction of the evil-doers, for the sake of firmly establishing the reign of truth, I am born from age to age" (Bhagavad-Gîta, IV, verses 7-8). And I could not help raising my mind to the eternal One, the Sustainer of the universe, by whatever name men might choose to call Him, and thinking: "Thou wert born in our age as Adolf Hitler, the Leader and Savior of the Aryan race. Glory to Thee, O Lord of all the worlds! And glory to Him!" A feeling of ecstatic joy lifted me above myself, like in India, nine years before, when I had heard the same fact stated for the first time in public, by one of the Hindus who realized, better than many Europeans, the meaning and magnitude of our Führer's mission. Never had I, perhaps, been so vividly aware of the continuity of the Aryan attitude to life from the earliest times to now; of the one more-than-human truth, of the one great ideal of more-than-human beauty, that underlies all expressions of typically Aryan genius, from the warrior-like piety of the Bhagavad-Gîta, to the fiery criticisms of misguided pacifism and the crystal-clear exhortations to selfless action in Mein Kampf.

I recalled the words: "Living in truth," the motto of King Akhnaton of Egypt -- perhaps the greatest known thinker of early Antiquity outside India. And I remembered how, according to most archaeologists, there is "no sense of sin" in the Religion of the Disk as Akhnaton conceived it; that it is "absolutely unmoral" (J. D. S. Pendlebury, in Tell-el-Amarna (1935), 156. Also Sir Wallis Budge in Tutankhamon, Amenism, Atenism and Egyptian Monotheism [1923], 114). And I thought: "It is to be expected. To 'live in truth' is not scrupulously to avoid lies and deceit and all manner of 'unfair' dealings, if these be expedient in the service of a higher purpose; it is not to mould one's conduct upon Moses' Ten Commandments and the nowadays accepted standards of Christian morality -- the only morality that most people, including archaeologists, can think of. It is to live in perfect accordance with one's place and mission in the scheme of things; in accordance with that which is called, in the Bhagavad-Gîta, one's svadharma, one's own duty. And another remark, of Professor Pendlebury, came to my memory, namely that this 'unmoral' character of King Akhnaton's solar religion "is enough to disprove any Syrian or Semitic origin of his movement." Others have seen in the young Pharaoh's reaction against the death-centered formalism typical of ancient Egypt before him and since, the proof of a definite Aryan influence from the kingdom of Mitanni. No one can yet tell whether such is the case. But undeniably, Akhnaton himself was partly Mitannian -- partly Aryan. I recalled the reverence in which the ancient Persians, who were Aryans, held the idea of truth for the sake of truth. And I thought: "There is only one morality in keeping with that cult of truth, which is also the cult of integral beauty; and that is the morality of detached action. The ethics of individual happiness, the ethics of the 'rights of man -- of every man -- are untrue. They proceed, directly or indirectly, from the ethics of Paul of Tarsus who preached that all nations had been created 'out of one blood' (Acts 17.26), by some all-too-human heavenly father, lover of all men. They proceed from the Jewish ethics -- that mockery of truth -- that put the inferior in the place of the superior and proclaim the Jewish race 'chosen' to rule the world, if not materially, at least in spirit. They are a trick of the cunning Jew, with a view to reverse for his own satisfaction, and ultimately for his own selfish ends, the divine order of Nature in, which men, as all creatures are different and unequal; in which nobody's 'happiness' counts, not even that of the highest men. "We have come to expose and to abolish those ethics of equality and of individual happiness which are, from time immemorial, the glaring antithesis of the Aryan conception of life. "It is the superior man's business to feel happy in the service of the highest purpose of Nature which is the return to original perfection -- to supermanhood. It is the business of every man to be happy to serve that purpose, directly or indirectly, from his natural place, which is the place his race gives him in the scheme of creation. And if he cannot be? Let him not be. Who cares? Time rolls on, just the same, marked by the great Individuals who have understood the true meaning of history, and striven to remold the earth according to the standards of the eternal Order, against the downward rush of decay, result of life in falsehood -- the Men against Time. "It is a man's own duty in the general scheme of creation that defines what are his rights. Never are the so-called 'rights' of his inferiors to define where lies his duty. "It is a race's own duty, its place and purpose in the general scheme of creation, that defines what are its rights. Never are the so-called 'rights' of the inferior races to define the duties of the higher ones. "The duty of the Aryan is to live consciously 'in truth,' ruling the rest of men, while raising himself, through detached action, to the state of supermanhood. The duty of the inferior races is to stay in their places. That is the only way they can also live 'in truth' -- indirectly. Aryan wisdom understood that, long ago, and organized India according to the principle of racial hierarchy, taking no account whatsoever of 'individual happiness' and of the 'value of every man as such.' "Alone in our times, we National Socialists militate in favor of an organization of the whole world on the basis of those self-same eternal principles; of that selfsame natural hierarchy. That is why our cause is the cause of truth. That is why we have the duty -- and therefore the right -- to do anything which is in the interest of our divine cause."

In a flash, I remembered my lost manuscript, and I continued thinking: "Yes, I can do anything provided I do it solely for the cause, and with detachment -- with serenity. Then -- but only then -- I am above all laws; or rather, submitted to one law, namely, to the law of obedience: of blind obedience to anyone who has authority over me in the National Socialist organization, in the case I am acting under orders; and in any other case, of absolute obedience to the commands of higher expediency, to the best of my own understanding of them. " Presently, if I am absolutely detached -- if I am free from all desire of personal recognition; free from all personal delight in deceiving our enemies; free from all personal pride, from all sense of personal importance as the author of my book -- then, and only then, I have the right, nay, the duty, to lie, to crawl, to make the otherwise most contemptible exhibition of myself, in order to, try to save my manuscripts from destruction .... "I must not feel 'clever' and be pleased with myself for deceiving the Governor. It is not my cleverness that did it: it is, through my agency, the unfailing, invisible Powers that watch over the interest of the cause of truth. I am, in all that, as it is written in the old Sanskrit Writ, nimitta matra -- nothing but an instrument. "I must, also, not feel sorry to break my word, and to repay the enemy's leniency with what the Democrats would call 'cynical ingratitude.' I am a fighter for the Nazi cause, openly at war with these people for the last ten years, and, from the day I was able to think, at war with the values that they stand for. All is fair in war. All is fair in our dealings with that world that we are out to remold or to destroy. There is only one law for us: expediency. And I am right, in the present circumstances, to act accordingly, not for myself, but in the interest of the sacred cause, remembering that I am an instrument in the service of truth; as it is written in the old Sanskrit Writ, nimitta matra -- nothing but an instrument. "And if I by some miracle, my book is saved, I must not feel happy in the expectation that one day, in a free Germany, my comrades will read it and think: 'What a wonderful person Savitri Devi Mukherji is, and how lucky we are to have her on our side!' No; never; it is I, on the contrary, who am privileged to be on the side of truth. Truth remains, even if people of far greater talent than I ignore it, deny it, or hate it. It is I who am honored to be among the élite of my race -- not my comrades, to have me among them. Any of them is as good as I, or better. "As for my book, without the inspiration given me by the invisible Powers I would never have been able to write it. The divine Powers have worked through me, as through thousands of others, for the ultimate triumph of the Nazi Idea. I have not to boast. I have but to thank the Gods for my privileges, and to adore. As it is written in the old Sanskrit Writ, I am nimitta matra -- nothing but an instrument in the hands of the immortal Gods." I also thought: "It is difficult to be absolutely detached. Yet it is the condition without which the right action loses its beauty -- and perhaps, sometimes also, a part of its efficiency. It is the condition without which the one who acts remains all-too-human; too human to be a worthy National Socialist. "It is, however, perhaps, even more difficult for a woman than for a man to remain constantly detached -- a serene instrument of duty and nothing else, day after day, all her life." From the depth of my heart rose the strongest, the sincerest craving of my whole being; the culminating aspiration of my life: "Oh, may I be that! In the service of, Hitler's divine Idea, may I be that, now, tomorrow, every day of my life; and in every one of my future lives, if I have any!"

Then again I thought of my other manuscripts; and I tried to maintain, with regard to their fate, that attitude of absolute detachment which is the attitude of the strong. "I have done my best to save them," reflected I. "I have lied; I have acted, without regretting it nor boasting inwardly of my cleverness." If I remain detached, surrendering "the fruits of action" -- the fate of my writings -- entirely to the higher invisible Powers, then and then alone I shall be worthy of the sacred Tradition of Aryandom; worthy of our Ideology, which is inspired by the same spirit. Nay then and then alone I shall be training myself to act with absolute detachment in the future, whatever I might be called to do for our cause: then and then alone, being selfless, I shall have the right to condone anything, and to do anything."

On Friday the 10th June I did not seek an interview with the Governor, although I knew be would come to the "Frauen Haus" ["Women's Wing" of the Werl Prison] on his weekly visit. I thought I would refrain from all further intervention in favor of my manuscripts. But when the Governor actually passed before my open cell in company of Fräulein S., Frau Oberin's assistant, and of the unavoidable interpreter, I somewhat could not help expressing the desire to speak to him. "My time is eleven o'clock," answered he roughly; "I cannot stop and speak to each prisoner according to her whims." And he walked past. But after a few minutes I was called and ushered into the recreation room where the three people I have just mentioned were standing. "Well, what is it you wish to tell me?" said Colonel Vickers before whom I stood, looking as dejected as I possibly could. "I only wished to ask you whether, perchance, you can give me any hope concerning the fate of my manuscripts," said I: "I have already told you that I do not intend to publish them. Yet the anguish at the thought that they might be destroyed allows me no rest, no sleep at night. I have put so much of my heart in these writings that I want to keep them, be they good or bad, as one wants to keep an old picture of one's self ..." Colonel Vickers gave me a keen glance and interrupted me: "You told me all that stuff the other day," said he. "I know it. And can't be always busying myself with your case and listening to your pleas. You don't seem to realize that you are no longer a free woman. You have forfeited your freedom by working to undermine our prestige and our authority in this conquered country -- a very serious offence, I would say a crime, in our eyes. Moreover, you despise us and our justice, in your heart. You had the cheek to tell me, the other day, to my face, that you hold the war-criminals to be innocent, after they were duly tried and duly sentenced by British courts, the fairest in the world. In this prison, in spite of your offence and of the heavy sentence pronounced against you -- the heaviest a British judge has given a woman for a political offence of that nature -- you were treated leniently. And you have repaid our kindness by writing things against us. "Do you think I am in a mood to read your damned Nazi propaganda for the sake of telling you how much I dislike it? I have more important things to do. I told you -- I gave you my word -- that I would call you to my office when I have read it. I shall read it when I please -- not when you tell me to. And that might be in three months' time, or in six; or in a year. You are here for three years. You must not imagine that we are going to release you without first being sure that you can harm us no longer. In the meantime, if you come bothering me again in connection with that manuscript of yours, I shall destroy it straight away. Why on earth should I be lenient towards you, may I ask you? I have seen two wars, both of them the outcome of that German militarism that you admire so wholeheartedly. Why should I show mercy to you who in your heart despise mercy, and mock humanity? To you, who sneer at the most elementary decent feelings and who have nothing but contempt for our standards of behavior? To you, the most objectionable-type of Nazi whom I have ever met?"' I kept my eyes downcast -- not to let Colonel Vickers see them shining with pride. Not a muscle of my face moved. To the extent that it was possible, I purposely thought of nothing; I tried to occupy my mind with the pattern of the carpet on which I stood, so that my face would remain expressionless at least as long as I was in the Governor's presence. But within my heart, irresistibly, rose a song of joy. "You can go," said Colonel Vickers addressing me after a second's pause. I bowed, and left the room. On the threshold of my cell, unable to contain myself any longer, I turned to the wardress who accompanied me. "You would never guess what a glorious compliment the Governor has just paid me!" exclaimed I. And a bright smile beautified my tired face. "No." She was astonished that the Governor could pay me any "compliment" after all that had happened, and specially after the recent search in my cell. "He told me," said I, "that I am the most objectionable type of Nazi that he has ever met " And I added, as she smiled in her turn at the sight of my pride: "When I was on remand, Stocks, who used to call me down to his office now and then, for a chat, once confided to me that, in 1945, there were eleven thousand SS men imprisoned here in Werl. It is not too bad an achievement, you know -- and specially for a non-German -- to be, in the eyes of a British officer, more 'objectionable' than eleven thousand SS men ... What do you think?" "I think you are unbeatable," replied the wardress, good-humoredly. In my cell, I pondered over the Governor's words. I now had almost the certitude that my manuscripts would be destroyed. Still, for a while, I forgot all about them in the joy and pride that I experienced as I weighed in my mind every sentence Colonel Vickers had addressed me: "You despise us and our justice, in your heart ..." "You sneer at the most elementary decent feelings, and have nothing, but contempt for our standards of behavior ..." There was at least, after the Public Prosecutor who had spoken at my trial, a man from the enemy's camp who seemed to understand me better than most people did outside Nazi circles. Far from telling me that I "surely did not mean" the "awful things" I said -- as the hundreds of intellectual imbeciles I met both in the East, and in the West -- this soldier did not even need to, hear me say the "awful things" in order to be convinced, that I meant them none the less. An intelligent man. He might not have wished to understand that the responsibility for this war rests with England rather than with Germany. But at least, he understood me. He seemed [no] longer to believe, as he had so naively a week before, that I "cannot but" look upon any human life as more sacred than that of a cat. Perhaps he had read enough of my book to lose his illusions on that point. Or perhaps someone -- Miss Taylor, or some other person connected with my trial -- had been kind enough to enlighten him. Anyhow, I felt genuinely grateful to him for his accurate estimation of me, for there is nothing I hate as much as being mistaken for a person who does not know what she wants. He understood me. And his words flattered me. His last sentence: "You are the most objectionable type of Nazi that I have ever met," was, in my eyes, the greatest tribute to my natural National Socialist orthodoxy yet ever paid to, me by an enemy of our cause. It occurred to me that Colonel Vickers had been in Germany since the Capitulation. Someone had told me so. Then, he must have met quite a number of my brothers -- in faith, even apart from the eleven thousand SS men that Mr. Stocks had mentioned. No doubt, he exaggerated a little when he declared me the "most objectionable" type of all. With the exception of my unfortunate collaborator Herr W. [Gerhard Wassner], who got caught for sticking up my posters in broad daylight, other Nazis are, as a rule, far more practical, and more subtle -- i.e., more intelligent -- than I. In which case they should be more "objectionable" than I, in a Democrat's eyes. But reflected I, most of them are Germans; and many have had the privilege of being brought up in a National Socialist atmosphere. That is somewhat of an excuse in the conception of the Democrats who have such a naïve confidence in the power of education. I, a non-German Aryan who never had the benefit of a Nazi training, came to Hitler's Ideology by myself, of my own free will, knowing, at certain of its fundamental traits, that I would find in it the answer to my strongest and deepest aspirations. And not only did I welcome the leadership of National Socialist Germany in Europe before and during the war, but I came and told the Germans now, after the war, after the Capitulation, after all the efforts of the victorious Allies to inculcate into them the love of parliamentarism, of everlasting peace, and of Jewish rule; "Hope and wait! You shall rise and conquer once more. For still you are the worthiest; more than ever the worthiest. And no one will be happier to see you at the head of the Western world. Heil Hitler!" In other words, repudiating, defying, reducing to naught my Judeo-Christian democratic education -- feeling and acting as though it had never existed -- I identified myself entirely with those who proclaimed the rights of Aryan blood, myself a living challenge to the defilement of the Aryan through education; a living proof of the invincibility of pure blood. And in addition to that, I pointed out how our National Socialist wisdom is nothing else but the immemorial Aryan Wisdom of detached violence, thus justifying in the light of the highest Tradition, all that we did, all that we might do in the future. From the democratic standpoint, perhaps that is, after all, more dangerous and therefore more "objectionable" than the so-called "war-crimes" that I had not the opportunity to commit. Perhaps Colonel Vickers had merely made a statement of fact, implicitly recognizing the meaning of my attitude, the meaning of my whole life. For which, again, I thanked him within my heart

But, as I said, I now felt sure that my precious book, my "best gift to Germany," would be destroyed. And although, on the evening of that day, Fräulein S. came to my cell to ask me to sign a paper in connection with my possible release, I soon outlived the joy that the Governor's words had provoked in me. In fact, my awareness of being so "objectionable" from the enemy's stand-point, made me deplore all the more the loss of my manuscripts, specially of Gold in the Furnace. I felt more than ever -- or imagined -- how much indeed I could, one day, on the eve of Germany's liberation, contribute to stir up National Socialist enthusiasm, through those pages, written with fervor. And the thought that I would be no longer able to do so distressed me. But then again I recalled the words of the ever-returning Savior, in the Bhagavad-Gîta: "Seek not the fruits of action ..." And I concentrated my mind on the teaching of serene service of truth regardless of success or failure; and I bent all my efforts on the renunciation of my book. "Break that last Lie that hinds you to the realm of consequences, and you will be free!" said the clear, serene voice within me, the voice of my better self. "Win that supreme victory over yourself, you who fear nothing and nobody, and you will be invincible; accept that supreme loss inflicted upon you by the enemies of the Nazi cause, you who have nothing else to lose but your writings; accept it as thousands of your comrades have accepted the loss of all they loved, and you will be worthy of your comrades, worthy of your cause. Remember, you who have come to work for the resurrection of National Socialist Germany, that only through the absolute renunciation of those who serve them to all earthly bondage, can the forces of Life triumph over the forces of death." And I recalled in my mind the beautiful myth of the visit of the Goddess Ishtar to the netherworld, as it is reported in the old Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh. To bring back to life her beloved, the God Tammuz -- the divine Youth Who dies every winter and rises in glory from the dead every spring -- Ishtar-Zarpanit, Goddess of love and war-Goddess of the double forces of creation: fecundity and selection -- went down to the netherland, attired in all her jewels. At the first gate, she left her ear-rings; at the second, she left her armlets; at the third, her bejeweled girdle; at the fourth, her necklaces, and so forth, until she reached the seventh and last gate. She left there her last and most precious jewel, and entered naked into the Chambers of the dead ... Then alone could she bring back to life the young God Tammuz -- invincible Life -- prisoner of the forces of death. "The price of resurrection is absolute renunciation, sacrifice to the end," thought I. "Inasmuch as they have retained something of the more ancient wisdom under their Jewish doctrine, even the Christians admit that." I felt an icy cold thrill run up my spine and an unsuspected power emerge from me. My mind went back to the unknown man of vision who wrote down the myth of Ishtar, seven thousand years ago, thus helping me to realize, today, in captivity, that unless I willingly despoiled myself of everything mine -- unless I looked upon nothing as mine -- I could not work for our second rising. I felt that I had come so that, through me, as through every true National Socialist, the eternal Forces of Life might call from the slumber of death the modern Prototype of higher mankind; the perfect god-like Youth, strong, comely, with hair like the Sun and eyes like stars and a body surpassing in beauty the bodies of all the man-made gods. I identified in my heart that creature of glory with the élite of Adolf Hitler's regenerate people. And I knew that the ever-recurring call to resurrection resounded today, through us, through me, as our battle-cry in the modern phase of the perennial struggle Deutschland erwache! ["Germany Awake!"]. And the voice of my better self told me: "Unless, you have sincerely, wholeheartedly, unconditionally, put aside your last and most precious treasure -- snapped your last tie with the world of the living -- the Prisoner of the forces of death will not come forth at your call. Come: free yourself once and for all of all regret, of all attachment: give tip your writings in sacrifice to the divine cause; and be, you too, a force of resurrection!'' Tears rolled down my cheeks. I pictured within my mind the face of our Führer -- stern, profoundly sad, pertaining to the beauty of things eternal -- against the background of his martyred country, first in flames and then in ruins; also against the background of those endless frozen white plains where snow covered the slain in battle, while the survivors of the Wehrmacht, of the SS regiments, of the Leibstandarte ["Body-guard"], that élite among the élite, driven further and further east as prisoners of war, went their way to a fate often worse than death. And I burst out sobbing at the memory of that complete sacrifice of millions, offered as the price of the resurrection of real Germany -- of Aryan man, the god-like youth of the world. I looked up to the Man who inspired such a sacrifice, after having, himself, sacrificed everything to the same great impersonal purpose; to Him, Who never found the price of resurrection too high. And once more I recognized in Him the Savior Who comes back, age after age, "to establish on earth the order of truth." I gave up all regret of my lost book. "Let them destroy it, if they must," thought I. And in an outburst of half-human half-religious love -- exactly as when faced with the threat of disfiguring torture, on the night of my arrest -- I uttered in my heart the supreme words: "Nothing is too beautiful, nothing is too precious for Thee, my Führer!" And again, as on that night, I felt happy, and invincible.

The preceding text is excerpted from chapter 12 of of Savitri Devi's Defiance (Calcutta: A.K. Mukherji, 1951). Savitri's footnotes have been incorporated in parentheses within the text; editorial additions appear in brackets. |

|

|